The Big Question: Why Top‑50 Still Feels So Far for Turkey

Let’s be honest: Turkish tennis has made visible progress by 2026, but there’s still no stable top‑50 player in either ATP or WTA singles. We see flashes – deep runs at ATP 250 events, solid ITF titles, a couple of Challenger trophies – yet no one stays in the elite zone long enough to change the narrative. The key question sounds simple: does Turkey actually have the ecosystem to grow a top‑50 player, or are local talents doomed to hover around the top‑150 mark? To answer that, we need to dissect coaching, infrastructure, competition level and, importantly, the economics behind a modern pro career.

Defining the Battlefield: What “Top‑50” Really Demands

Basic Terms Without the Jargon Fog

ATP and WTA rankings are rolling 52‑week systems: every tournament gives points, and older results drop off week by week. Top‑50 in singles usually means you’re seeded at Grand Slams, almost always directly accepted into main draws of ATP 500, WTA 500 and many ATP/WTA 250 events. Statistically, top‑50 players win matches at a roughly 55–60% rate across a season, not 80–90%. The difference from a top‑150 athlete is less about talent and more about sustaining that win rate across surfaces, continents and pressure situations while staying healthy almost year‑round.

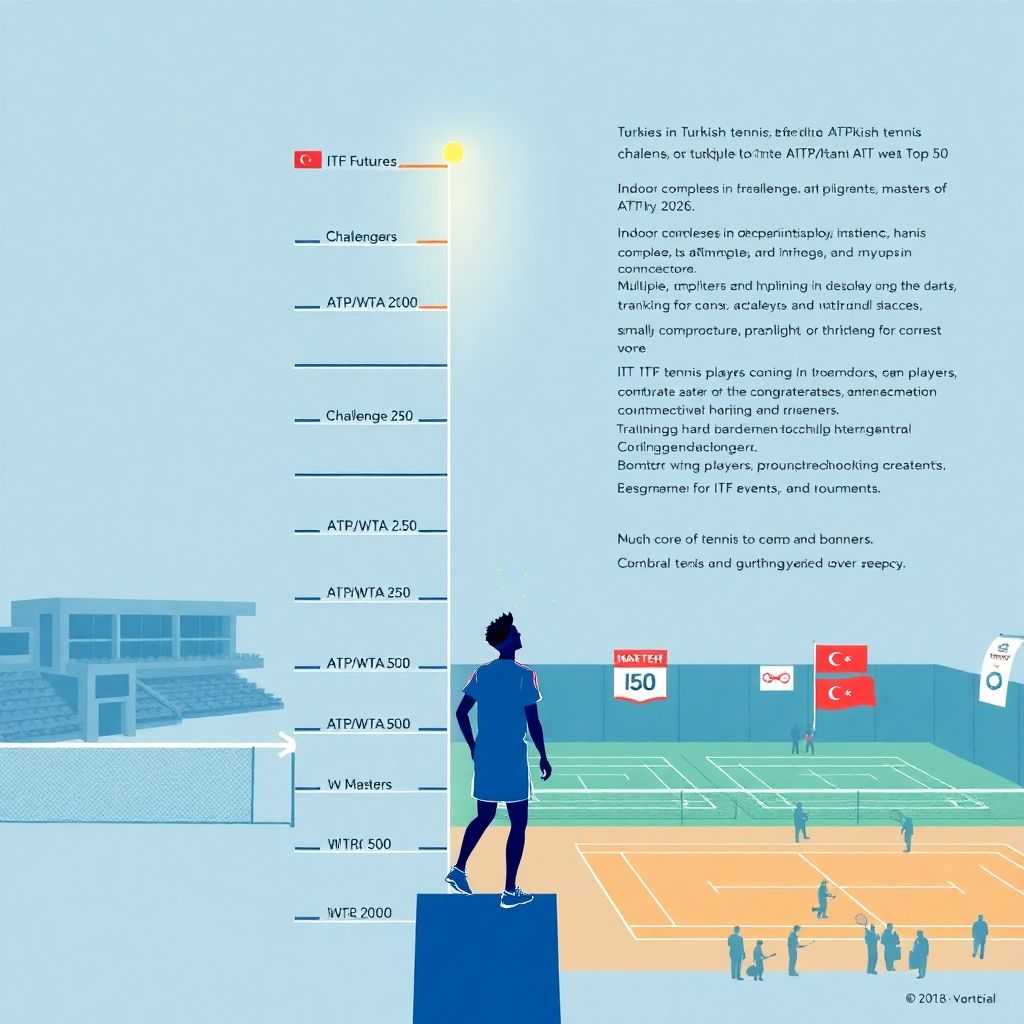

Performance Ladder: A Text Diagram

Imagine the path as a vertical ladder, where each rung has a typical ranking band and prize money window:

1) ITF Futures: #600–#1500 – survival mode

2) Challengers: #120–#400 – first real income

3) ATP 250 / WTA 250: #40–#120 – gateway to the elite

4) ATP 500 / WTA 500: #15–#60 – daily contact with top guns

5) Masters / WTA 1000: #1–#40 – the real spotlight.

For a Turkish player, the challenge is not touching each rung once, but cycling sustainably between levels 2–4 without financial collapse or coaching downgrades.

Where Turkey Stands in 2026: Solid Base, Thin Peak

Infrastructure Boom, Elite Result Gap

Over the last decade, Turkey quietly turned into a regional hub for the sport. New indoor complexes in Antalya, Istanbul and Izmir, improved clay and hard courts, more qualified fitness coaches: all of this pushed the average level up. Juniors from Central Asia, the Middle East and Eastern Europe increasingly treat the country as a training and competition base. Yet if you look purely at rankings, Turkish athletes still sit mostly in the #80–#300 corridor, with occasional spikes higher. The base of the pyramid widened, but the tip – consistent ATP/WTA second‑week players – remains fragile.

Comparing with Similar Tennis Nations

To understand the ceiling, it helps to compare Turkey with countries that had similar starting points around 2005–2010: think of Kazakhstan, Poland or even Greece. All three turned scattered talent into top‑10 stars within fifteen years. Their recipe usually combined heavy federation backing, foreign coaches with Grand Slam experience and aggressive scheduling at higher‑tier events. Turkey matched them in building courts and hosting events, but lagged in long‑term individual investment at the moment when a promising player moves from junior slam quarterfinalist to full‑time pro status, which is the most fragile career stage.

Academies and Camps: Strong Midfield, Few Finishers

How Turkish Academies Actually Work

Many people hear about tennis academies in turkey for professional players and imagine a copy of Nadal’s academy in Manacor. In reality, local centers usually mix performance groups with recreational kids, because that keeps the lights on financially. Weekly volume of court hours is often enough; the problem is the quality and specificity of those hours. A 19‑year‑old ranked around #350 ATP doesn’t just need generic drills; he needs high‑intensity point construction, detailed video analytics, surface‑specific patterns and targeted match play vs opponents ranked 50–150 spots higher, which is not always available in domestic setups.

Training Camps as Seasonal Boosters

One positive trend by 2026 is the rise of winter and pre‑season gatherings that brand themselves as some of the best tennis training camps in turkey. Their biggest strength is variety: you can see ITF juniors rallying with Challenger regulars, plus visiting pros from Germany or Russia escaping colder climates. Short, two‑week blocks with combined fitness testing, nutrition consultations and load monitoring definitely raise standards. However, camps are bursts of intensity; they don’t replace a year‑round performance system with clear ranking goals, periodization and psychological support, which is what it takes to crack and hold top‑50 level.

Coaching and Methodology: Can Local Know‑How Scale Up?

What “ATP/WTA‑Level Coaching” Really Means

There’s a huge difference between “good club coach” and a mentor calibrated for top‑100 battles. turkey tennis coaching programs for atp wta level must juggle biomechanics, data analytics, travel logistics, as well as injury prevention. Crucially, they have to understand how a top‑50 baseline looks in raw numbers: average rally length on hard court, expected break‑point conversion, forehand speeds under pressure. Some Turkish coaches already track these metrics with video and wearable tech, but the ecosystem still relies heavily on intuition. Until evidence‑driven feedback becomes routine, players will keep losing marginal matches that define ranking jumps.

Importing Expertise vs Growing Your Own

Kazakhstan showed one model: import established foreign players and coaches, then localize the know‑how. Turkey tried a softer variant – short‑term partnerships with European experts and traveling coaches. The upside is quick knowledge transfer; the downside is lack of continuity. After one or two seasons, many players bounce between different voices, each tweaking technique and tactics. Top‑50 projects need a stable “performance team” lasting at least four years: main coach, fitness trainer, physio and mental specialist working towards the same metrics. At the moment, only a few Turkish prospects enjoy that level of continuity.

Money, Scholarships and the Hard Math of a Pro Career

True Cost of Chasing Top‑50

A serious singles campaign from age 18 to 23 easily burns through 400–600 thousand dollars, even with careful budgeting. That includes travel to Challengers on several continents, physio support during long swings and enough recovery blocks to avoid chronic overuse injuries. National federation help and sponsorships cover only part of that bill. Families often underestimate how long it takes to break into profitable ranking zones. As a result, players from financially average backgrounds tend to stop pushing aggressively once they reach a modest profit line around top‑200, which quietly kills many potential top‑50 trajectories.

Scholarships and Hybrid Pathways

One way Turkey tries to soften this problem is through tennis scholarships in turkey for international players at universities with strong sports departments. For foreign athletes, this is attractive: relatively affordable education, plenty of ITF events nearby and access to local coaches. For Turkish players, however, the college path can be a double‑edged sword. If the program is structured around a heavy domestic league schedule, the athlete might plateau at a level good for university competition but not aggressive enough for a top‑100 push. Hybrid models – two years of college, then full‑time pro – are slowly gaining popularity.

Tournaments at Home: Advantage or Comfort Trap?

Density of Events on Turkish Soil

On paper, Turkey is a dream location for stacking match experience. There are numerous ITF 15K and 25K tournaments, plus several Challenger stops and mid‑level women’s events spread across the year. Add to that a packed calendar of professional tennis tournaments in turkey 2024 and beyond, including indoor swings in Istanbul and resort‑based weeks in Antalya. The practical upside is clear: local players can chase points with minimal travel stress and costs. They build confidence, collect ranking positions and gain familiarity with conditions that suit their style, particularly slow and medium‑speed outdoor hard courts.

Why Too Much Home Comfort Can Backfire

The flip side appears when these domestic successes aren’t followed by consistent exposure to tougher draws abroad. You can be a “local boss” at home Challengers yet struggle badly when facing top‑70 opponents in Europe or North America. The rhythm, court pace and even umpiring standards differ. Without regular foreign swings, Turkish players become over‑specialized in one competitive environment, which lowers their resilience in five‑set qualifiers, loud stadiums and windy outdoor conditions on unfamiliar courts. Top‑50 players, by contrast, must be nomads by default, comfortable with constant adaptation and daily uncertainty.

So, Can Turkish Players Really Crack the Top‑50?

Short‑Term Outlook: Chances for a Breakthrough

Given current trajectories, it’s realistic to expect at least one Turkish player – maybe two – to touch the lower edge of the top‑50 in singles within the next five to seven years. The ingredients are getting closer: better physical conditioning norms, more data‑driven training blocks, smarter scheduling and use of high‑altitude or fast‑court swings to accumulate points. The breakthrough is most likely to come from a player already flirting with top‑80 right now, provided they stay injury‑free and secure funding to travel with a stable team rather than cutting corners on professional support.

Long‑Term Conditions for Sustainable Presence

The real test is not whether Turkey produces a single star but whether it can maintain a rotation of three to five players in the #30–#80 range across both tours. For that, the system must upgrade in three areas: coach education that’s tightly linked to international best practice, stronger coordination between academies and federation on individual long‑term plans, and risk‑sharing financial tools so that one bad season doesn’t end a promising career. If these structural shifts continue at the current pace or faster, Turkey can realistically move from a “hosting country” to a genuine producer of stable top‑50 ATP and WTA talents.