From Dusty Village Roads to Floodlit Arenas

If you really want to understand Turkey, skip the postcard bazaar clichés and go watch a village race on a religious holiday. Long before glossy stadiums, kids were sprinting on dirt roads for a plate of baklava and local bragging rights. Those informal duels – often tied to harvest festivals or weddings – created a quiet expectation: every community has at least one “fast one”. That social role of the local hero is what later fed high‑school teams, city clubs and finally national squads traveling to Diamond League meets. When we talk about the cultural side of athletics in Turkey, we are not just describing a sport; we are tracing a social ladder that starts with barefoot sprints and ends with athletes walking into Olympic stadiums in national colors.

Numbers Behind the Culture: What the Stats Actually Say

Let’s ground the romance in data. According to the Turkish Athletic Federation, the number of licensed track and field athletes has grown from roughly 60,000 a decade ago to well over 200,000 today, with running events drawing tens of thousands of recreational participants each year. Istanbul Marathon alone typically gathers around 40,000–45,000 runners, and major city 10Ks in Izmir, Ankara and Antalya are rapidly catching up. Youth participation is especially telling: in some provinces more than half of registered athletes are under 18, which suggests that athletics is quietly competing with football for after‑school attention. These numbers show that what started as local fun runs has become a mass movement cutting across regions and income levels.

Village Races as Social Glue

In small Anatolian towns, the annual race is less about medals and more about social choreography. Elders line the streets; tea houses turn into improvised VIP lounges; local businesses sponsor T‑shirts instead of billboards. Races around Bayram holidays or municipal festivals function as intergenerational meetings where grandparents cheer for the same kids they scold for playing outside too long. There is no formal talk of talent identification, yet that is exactly what happens when a fast 14‑year‑old from a mountainous village gets noticed by a visiting PE teacher or a regional coach. If you are designing modern athletics training camps in Turkey and ignore these informal ecosystems, you miss the most efficient and culturally rooted scouting network the country has.

From Regional Meets to International Calendars

Over the past fifteen years, Turkey has moved from hosting mostly domestic championships to placing itself firmly on the international calendar. The indoor arena in Istanbul and renovated stadiums in cities like Konya and Bursa now attract Balkan, European and age‑group events, creating a pipeline: village race → provincial meet → national championship → international competition. This pyramid is not just athletic; it is symbolic. When a young runner from a remote Black Sea village sees their region listed next to Berlin and Doha on a meet calendar, the psychological horizon shifts. That change in self‑perception is hard to quantify, yet it directly feeds motivation, retention and the willingness of families to support demanding training schedules.

Economic Layers: More Than Ticket Sales

Athletics in Turkey is becoming an economic ecosystem with many small but connected streams. Large road races bring in hotel bookings, restaurant revenue and local transport income, especially in coastal cities where tourism overlaps with competition dates. Sports brands use Turkish events as test beds for shoes suited to mixed terrain and hot climates, while local SMEs sponsor school races as part of their marketing. For foreign organizers looking to book track and field stadiums in Turkey, the cost–benefit balance is attractive: facilities are modern, labor and logistics are comparatively affordable, and there is an enthusiastic volunteer base. All of this means that every new race on the calendar is also a micro‑economic development project for its host city.

Sports Tourism, But Done Smarter

Classic sports tourism sells “run a race, see a mosque, eat kebab”. That model is getting tired, and Turkey has the chance to upgrade it. Instead of generic weekends, imagine carefully curated sports culture tours in Turkey: morning workouts with local clubs, afternoons in neighborhood markets, evenings listening to athletes talk about how running changed their village status. Some agencies are already experimenting with more thoughtful sports tourism packages Turkey athletics enthusiasts can book—combining altitude training in eastern highlands, historical walks in Cappadocia and participation in a local 10K. The key instructional insight here: stop treating runners as tourists who happen to run; treat them as curious learners who want to understand how a country moves, eats and celebrates.

Forecasts: Where the Next Decade Might Go

Looking ahead, it is reasonable to expect continued annual growth in participation for road races, likely in the 5–8% range if economic conditions remain stable. Youth athletics should expand as long as schools keep improving facilities and cities invest in safe running routes. By 2030, Turkey could position itself as a top European hub for altitude and warm‑weather preparation, competing with places like Portugal and Kenya for international teams. To get there, planners need to bundle climate advantage, relatively low costs and cultural richness into coherent offerings. If regional federations coordinate calendars and data collection, the country can better forecast demand, calibrate infrastructure spending and avoid overbuilding prestige stadiums that sit half‑empty most of the year.

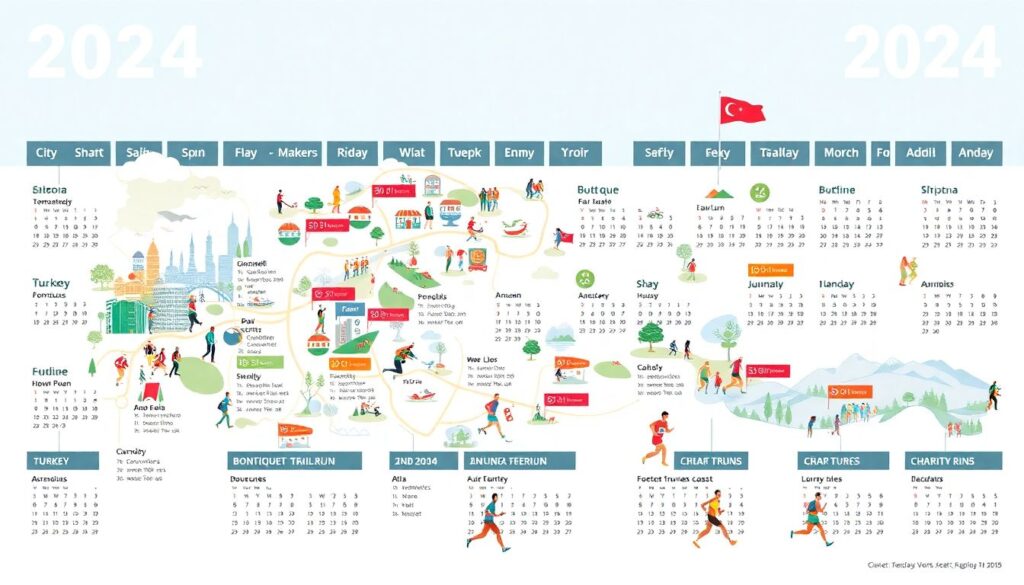

2024 as a Turning Point for Events

The calendar of running events and races in Turkey 2024 illustrates a shift from a few flagship races to a dense, tiered system. You now see city‑branded half marathons, boutique trail runs in tourist regions and charity runs tied to environmental or social causes. This diversity is healthy but risky: overcrowding the calendar can dilute sponsorship and media attention. Organizers should think more like ecosystem gardeners—spacing events, differentiating formats, and sharing data on participant demographics instead of competing blindly. Done right, this coordination transforms 2024 from “just another busy year” into the moment when Turkey proves it can host a coherent, sustainable national running circuit that still leaves room for charmingly chaotic village meets.

Influence on the Wider Sports and Leisure Industry

As athletics grows, it quietly rewires habits beyond the track. Urban planners start to hear citizens ask for running lanes rather than just car parks; apparel designers experiment with modest but performance‑oriented women’s kit; wellness influencers swap purely aesthetic goals for 5K and 10K training plans. Gyms add track‑oriented strength classes, and physiotherapists build specializations around endurance athletes. When foreign clubs come for preseason at athletics training camps in Turkey, they do not just spend money on hotels; they pressure local service providers to upgrade nutrition options, recovery services and multilingual staff. Those improvements then benefit domestic athletes and even non‑sport tourists, amplifying the overall impact on the hospitality and wellness sectors.

Unconventional Ideas to Push the Culture Forward

If you want Turkey’s athletics culture to mature faster, standard solutions—more races, bigger prize money—won’t be enough. One unconventional path is to integrate athletics with heritage management: use historic caravan routes and Roman roads as officially measured training loops, making each workout a lesson in local history. Another is to encourage municipalities to book track and field stadiums in Turkey for mixed‑use evenings: half the track reserved for club training, the infield used for community yoga or concerts, turning the stadium into a social hub rather than a sealed‑off elite space. Tech startups could build apps that match visiting runners with local guides, layering storytelling onto tempo runs instead of separating “tour” from “training”.

Practical Takeaways for Stakeholders

If you are a coach, treat Turkey not just as a cheap training destination but as a living classroom: design sessions that engage with local customs, altitudes and food, so athletes absorb more than mileage. Event organizers should pivot from one‑off spectacles to multi‑year partnerships with towns, ensuring that each race invests in school programs or basic facilities. Travel companies can evolve beyond generic itineraries and craft modular sports tourism packages Turkey athletics fans can customize—choosing between coastal intervals, mountain trails and cultural workshops. And for adventurous visitors, don’t wait for polished brochures: look for grassroots meets, ask locals about village races, and build your own informal version of sports culture tours in Turkey that starts where the asphalt ends and the stories begin.